Want to know how handpans are created and what are they made from? Puzzled by how they can sing like an angel wrapped in velvet but also rock some mean beats like a Dennis Chambers’ drum riff? Then read my article.

I’ll admit it, I’m fascinated by the physics of handpans: how they are made, their resonance (length of the sound of a note after it is struck), dynamics (volume loudness/softness) and harmonics (varying pitches of sound); and the differences between all the pans. What I’m about to tell you might be a bit geeky 😀, but I hope you find it interesting and learn some cool stuff!

The handpan world has traditionally been clothed in secrecy. From the original, patented Hang® to new craftsmen and women with their own closely-protected methods, it has been hard to discover details about the workings of these beautiful instruments. But from handpan co-operatives and other expert souls who have been willing to share, we now know more than ever before.

Most handpans are between 45-60cm in diameter. They are made from raw/regular steel, nitrided steel or stainless steel (learn more on Stainless Steel Handpans) in varying thicknesses and qualities and consist of two convex (domed) shells glued together.

The shells

The shells start as flat sheets that can either be Hand sunk, Spun or Rolled, Deep Drawn or Hydroformed into shape.

Hand Sunk Shells

Hand sunk shells are made with a manual or pneumatic/air hammer. It takes thousands of strikes to mould just one half-shell, which means a lot of time and muscle, but many makers prefer this method as it is faithful to the original steelpan production. Without the need for an expensive kit, it also creates a truly unique sound and appearance in each instrument.

Spun Shells

Next up, we have Spun shells. These are made by securing a metal disc on a lathe which makes it spin round. A special tool called a buck is then held against it starting from the middle of the disc slowly going to the outside, thereby forming the metal in the bowl/shell shape as it keeps spinning round. These Spun shells are a cousin to the Rolled shells patented by Pantheon Steel (of Halo fame), which use specially-adapted spinning machinery to different rotations per minute and also vary the way in which the shell is held and formed.

Deep Drawn Shells

Panart’s first Hanghang® were made with deep drawn shells. This method of making shells was later initiated by a group of European makers including Shellopan and Ayasa and is favoured by the likes of Saraz and many others. This method involves a custom-made mould in the shape of a shell and rings which are fitted in a large industrial deep drawing press that stamps out the shape in a matter of seconds.

Deep drawing has the advantage that extra material from the disc is able to slip through the rings so that the shape of the shell is not only formed by stretching the material but by the extra material flowing in, ensuring even distribution of thickness and consistent quality. The biggest producer of deep drawn shells is Ayasa Instruments, (starting) makers can buy their shells of different materials directly from them.

Hydroformed Shells

And last, but not least, is the method of forming shells with water under pressure. Sunpan was the first to use this method for making stainless steel shells for their special type of handpan. Renowned player and maker Colin Foulke made his 2015 designs available to the public of a hydroforming method using water from a household pressure-washer. Add two sturdy frames, 24 enormous bolts, a lot of genius and a few mistakes and mops and your shells are formed within minutes. Hydroforming is a great method and the results are quite similar to deep drawing steel, with hydroforming the thickness is a little less equal and the steel is stretched a little more.

The notes

Now we have the shells, it’s time to add sweet music. Creating and tuning each note is the hardest and slowest part of the process. The ‘holy grails’ for makers are clarity, stability and depth of tone, distinctive harmonics and overtones, rich resonance and zero crosstalk (where the sound from one note interferes negatively with another). By the way, if you need a little reminder on all those technical words, read our handpan glossary of terms.

The less stress or hammer strikes you make during the tuning process, the better. Many makers kiln-bake their pans several times during this phase to ensure durability of tuning. Here's a pretty interesting video from Numen Instruments:

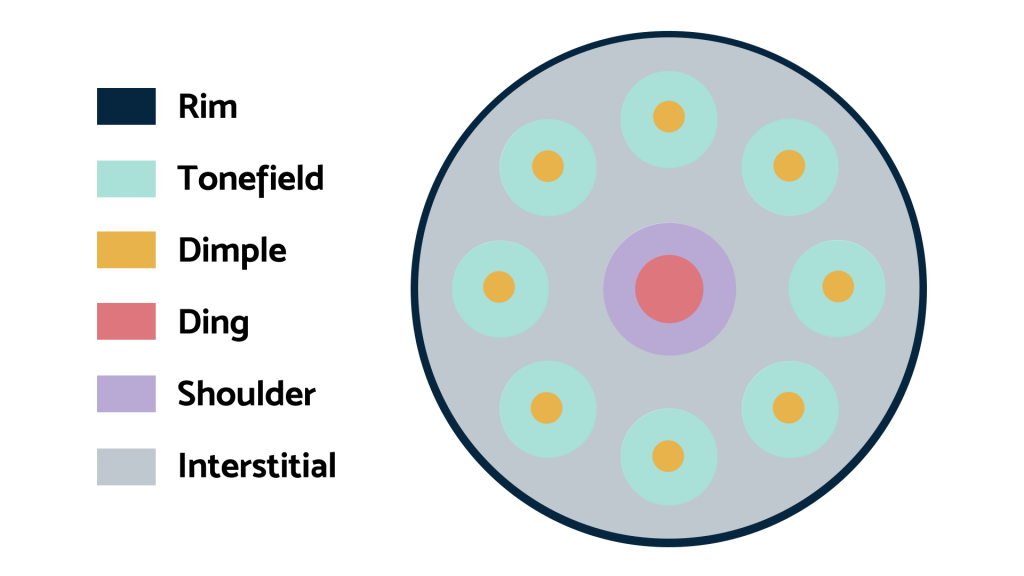

On the top shell, the central note is called the Ding. This is the lowest and usually most resonant note and the majority of them are convex, although some makers prefer the concave version. These two styles are informally called ‘outies’ and ‘innies’ just like belly buttons 😀

With the right technique and enough friction (from dry hands, a bit of rosin or a violin bow), you can make the Ding ring like a singing bowl.

Immediately surrounding the Ding is the ‘shoulder’ – the flat part that can produce a wide range of percussive sounds and, with a bit of practice and technique, higher 5th and octave harmonics.

In a circular pattern around the Ding shell are anywhere between 6-15+ concave notes that look like dimples. These, in turn, are surrounded by ‘tone fields’ – the flat parts around the notes that produce more percussive qualities, like the shoulder of the Ding.

When played in a left-right-left-right pattern from the biggest (deepest) to the smallest (highest), the notes form a scale. Without the restrictions of many instruments, handpan scales can be both major and minor and cover practically every type of music, from jazz to reggae, melancholic, meditative, celtic and middle eastern.

Finally, on the bottom shell, there’s a tuned sound-hole called the Gu, which produces a bassy note. The sounds are made via a cupping technique of the hand producing ‘Helmholtz resonance’ - that’s where you get a ‘wind throb’ effect similar to blowing over the top of an empty bottle.

It is also becoming popular for makers to put extra notes on the bottom.

In addition to the areas with notes, and those parts that produce harmonics, depending on where and how you touch it, you can get many incredible percussive sounds from a handpan. Handpan Players frequently utilise the edges of the Ding shell or the area between the shoulder and the tone fields to produce an incredible range of slaps, beats and knocks; using fingers, palms, knuckles and even elbows!

There’s also the Gu side that is like another instrument in itself and is often used in jams as a percussive accompaniment to other instruments. The handpan isn’t technically a drum, but it can certainly behave like one!

Check out this video from one of MasterTheHandpan.com’s teachers, Kabeção :

The Frequency

And finally, for the music nerds amongst us, there’s frequency. The handpan belongs to the idiophone family, that is any instrument creating sound primarily by the whole instrument vibrating, rather than the strings, air, or membranes.

Most handpans are tuned to 440Hz (Hertz, that is the frequency of sound waves) but there’s also the option of 432Hz pans that don’t jam with the 440Hz pans but sound amazing.

So there we have it – a basic summation of the rainbow of sounds that a handpan can produce. Quality of material, shell construction and tuning, maker skill and a little bit of magic, mean they can sing like no other instrument on earth.

By the way, I know shopping for a handpan can be overwhelming, but this complete guide will help you make the best decision for your future purchase.

Cover Picture : Hannah Rajah